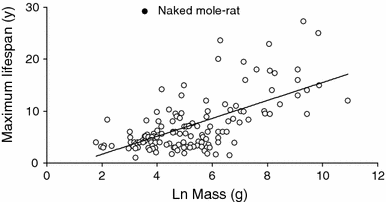

This figure (Buffenstein, 2008) shows maximum lifespan as a function of body mass of rodents. The naked mole rat maximum lifespan lies more than two standard deviations away from the trend line, according to the author. Naked mole rats also exhibit "negligible senescence" where the likelihood of death does not increase with age, while most other organisms including humans have exponentially increasing mortality rates.

I heard the author, Shelley Buffenstein, speak today at UW Nathan Shock Center 2022 Annual Geroscience Symposium. I almost skipped the talk (meh title). She was terrific. She is a world expert on the biology of naked mole rats. She recently published a book summarizing much of her research, The Extraordinary Biology of Naked Mole Rats. She spent the last 7 years at Calico (why did she leave?), and now is at University of Chicago. She has been publishing on the naked mole rat since at least 1991.

She shared this figure in her talk. It describes her view on how naked mole rats are able to achieve slower aging, including a more stable genome, transcriptome and proteome.

(Buffenstein, 2022)

Two parts were especially interesting. The first is the more stable cell cycle to avoid cancer. The second is the more stable proteome. The more stable proteome includes less protein synthesis, higher translational accuracy, upregulated HSP70 and HSP27, increased autophagy, increased proteosome activity and upregulated NRF2 and antioxidants. She shared data that the prevalence of misfolded proteins is much lower than in mice generally and in response to stress. I imagine the proteome of a naked mole rat to a city with new buildings, no traffic and no trash on the street, while the proteome of a mouse (and human) a crowded, messy city in disrepair.

How can humans get a more orderly proteome? We hear that diet, exercise and other aging-related compounds can help with things like autophagy. But how do we supercharge these pathways that seem to slow disorder and disease?

Evolution is smarter than we are. Evolution has figured out longevity pathways in naked mole rats, as well as other organisms. For example, Shelley described that when bears hibernate and don't move for six months, they don't lose bone mass, while humans do. As another example, elephants have double copies of the p53 gene, which reduces cancer risk.

How can we bring evolution's brilliant longevity discoveries into humans?

References:

Buffenstein, R. Negligible senescence in the longest living rodent, the naked mole-rat: insights from a successfully aging species. J Comp Physiol B 178, 439–445 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00360-007-0237-5